I turn 46 in December, and, in January, I’ll be racing a 31 year-old friend, Chris Brewer, who was a distinguished runner at the University of Oregon. It’s mostly a matter of pride, but there is a wager in play. I roughly breakeven if I avoid getting lapped twice in a 5k (on a standard 400 meter track) and I win fairly big if I avoid getting lapped once. He wins big if he laps me twice.

We started the challenge in September, and what makes it interesting is that Chris, by his own admission, had gotten quite out of shape. I imagine I would have won a 5k race with no handicap in September. On a DEXA scan, he might have had a body fat percentage in the mid 20s, while I would have been right around 20%.

A few years ago, I ran a 19:45 3-mile on a track (that would be a 20:34 5k). I think I’m just a fraction slower than that at the moment (perhaps 21min for a 5k). This is a post about my process for prepping the 5k three years ago:

I did take HGH while I was doing that training, and we have stipulated no performance enhancing drugs of any kind for this challenge. At the time, I estimated that HGH was worth about 30 seconds for a 5k based on some data that I had on and off.

Not everyone is going to be interested in all aspects of this post, so I’m going to cut it into sections.

Why should you care about your 5k time?

In Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity, Peter Attia says that the variable with the single highest predictive ability for longevity is a person’s VO2 Max (cardiac capacity). If you wanted to know a person’s expected lifespan, you get pretty far by simply knowing their age, sex, and mile time.

How does having a challenge or bet help motivation?

Almost every aspect of training and cutting weight is terrible, and a challenge or bet helps you make better decisions at the margin. You run for an hour when you would run for 30min; you avoid the worst eating and drinking mistakes; you occasionally do the super hard training that you would never do in the absence of a challenge.

Age and the 5k

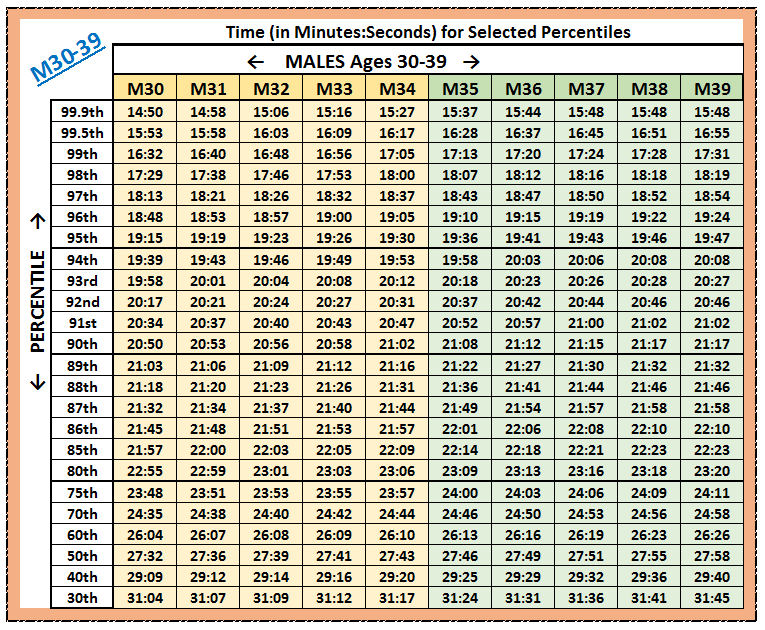

Age is disastrous for your 5k time. The data below, lifted from www.bigdatarunning.com, shows competitive 5k times as a function of age. The primary reasons for the declines seem to be: VO2 Max decline (maximum oxygen uptake decreases by about 1% per year on average), reduced cardiac output (lower max heart rate with age), loss of muscle fiber and strength reduction, and decreased mitochondrial efficiency.

Cutting Weight

Whenever you have a near term fitness goal involving cardio, you will want to cut weight. If there were no cost to this in terms of decreased energy, you’d want to cut weight quite aggressively. Fat is non-functional mass that will only hurt you on the track. VO2 Max is expressed in milligrams of oxygen consumed per kilogram of body weight. Intelligent weight reduction should decrease weight (the denominator in the VO2 max calculation) while keeping the numerator the same. This is one reason why fat reduction almost always leads to VO2 Max and mile time or 5k improvement.

The problem, as I detailed in my 2022 post about 5k training, is that cutting weight is miserable and has high costs in terms of your training schedule. I carry high body fat because I love to eat and drink, but I’ve had a ton of experience cutting weight, and what I can tell you is that the experience is the same for me almost every time: no matter what method or pace I choose, I experience significant cost when my cumulative calorie deficit exceeds 10,000 calories. So losing 10 pounds (35000 calories=10 pounds) will usually entail five or six weeks of being hungry, not thinking well, not training well, and not feeling well. I can mitigate this, fractionally, by being vigilant about maximizing the nutrient-to-calorie ratio.

When you’re cutting weight, you’re simply not capable of much in terms of training. The last time I cut weight, I was doing 70 minute beach runs early in the cut. After 10k calories, I’d be dead tired at 40 minutes and would usually quit at that point. I tried many alterations including different types of meals before, and even snacks during, and nothing made a difference.

In a recent Twitter post, Chris said, “Have about 20lbs left to lose which equates to 2 minutes or so on its own.” I haven’t seen that data (equating 10lbs of weight with a 1min improvement in the 5k) but that sounds roughly correct. Some of that 10lb is going to be muscle, probably 3.5-5 pounds, but the 5k time should still improve. Following Chris Twitter updates (@Chris_D_Brewer), his plan seems to be straight-line weight loss going into the race (equating to a total of almost 35 pounds in 3-4 months) while training hard the whole way through. I didn’t think that was possible, but he seems to be doing it so far.

Optimal Training vs My Approach

Optimal training for a 5k should be a mix of low-stress, Zone 2 cardio (4-5 times per week) with very high stress, super difficult interval training on a track (1-2 times per week).

This is not my approach. I don’t feel intuitively as I’m making improvements when I train Zone 2, and I also find it difficult to execute the super difficult interval training. It’s simply too taxing and unpleasant; the process of stopping and then starting again is too great a test of willpower.

If the willpower is there, a couple of people have told me that the optimum protocol for improving VO2 Max is the Norwegian 4X4 protocol. You run for four minutes at your max, then walk or jog lightly for three minutes. You repeat that four times. The four minute pace should be close to your max (peaking at 90-95% of max heart rate).

I like to do is very high intensity treadmill runs 4-5 times a week. Currently I’m doing 8-min pace for 32 to 56 minutes. If it’s 32 min, one or two of the miles will be at a 7min pace. When we get closer to the race, my preferred training is to actually do the thing… In this case, run 3miles at my fastest pace. I’ll try to do that five or six times in the month before the race. My belief is: If you’re racing the mile, practice running the mile; if you’re racing a 10k, practice racing the 10k. I believe this because the pain profile of each particular distance is unique, and you’ll be better off being well-acquainted with that exact pain profile.

I’m a big fan of the Alex Hutchinson book Endure. The main point of his book is that running is largely mental. The brain doesn’t like it when you run - the survival imperative is threatened by the rapid increase in heart rate and body temperature - and it wants you to shut down as soon as possible. Racing is largely a matter of overriding the conservative nature of brain, but not overriding it so much that you meet the very real physical constraint of going anaerobic too early. For managing this balance, there’s no substitute for practicing the exact distance that you will run.

Goals

My original goal was to be able to run three miles in 18 min in Jan. I have done enough running in the past two months to make me think that this is not going to be possible. Perhaps five years ago, with optimal process, it was possible to get there in 4-5 months. Now I think a more reasonable goal is a sub-19min three mile. That’s a 6:20 pace. If I can maintain that in the race with Chris, he’d need to run just better than a 5:20 pace to lap me twice, or just better than 5:50 to lap me once.

It seems like a well-designed challenge. Arguably I was the favorite at the time we made the bet, but now that it seems clear from Chris’ Twitter that he’s going to put in the work, it’s probably very close to even money. He might even be in a favorite if he doesn’t get injured (he should be way more likely to get injured than me, given the relative starting points).

Just as an aside, Chris must have incredible running talent to make this bet. Imagine I run at a slower pace of 20min for 3miles. At that pace, he’d need to run at a 5:36 pace to lap me twice. If you’re fit, go to the track and try to run one lap at that pace (1:24), then just imagine rolling that for 12.5 laps. The seconds start getting somewhat hard to come by in that range, such that 1:20 and 1:24 feel quite different. That’s the case for me pushing hard to get down to 6:20 pace or better.

The Case for Random Fitness Challenges

In sum, fitness challenges of this type are good because the goal itself is very much worth achieving (in this case, you’ll be healthier and you’ll probably live longer if your cardio improves), and the level of pain required to get there likely will not happen in the absence of a challenge. It helps if it’s a public challenge, because in that case the embarrassment that would occur if you did no training is a powerful motivator.

Postscript: I’m doing a version of November Writing Month where I’m going to blog every weekday in Nov (except for Thanksgiving and the day after). About half of the posts will be econ/finance, and the others will be on random topics. Unsubscribe if you don’t want all of that hitting your inbox this month!

Enjoyed the article Brandon and look forward to reading more on your other subjects this month which also interest me. One thing I’d disagree with you on this one is injury risk. Large difference in risk for 46 v 31 year old, especially if you’re hitting it hard four to five times a week instead of doing some easy runs in between. Totally agree with you on calorie deficit, I am a zombie when I’m eating less than 2500 cals a day for more than two or three days. Best of luck in your race!