In the traditional von Mises view of a crack-up boom, there is a somewhat violent dissolution of the existing monetary system. Von Mises: “The monetary system breaks down; all transactions in the money concerned cease; a panic makes its purchasing power vanish altogether.”

I think a crack-up boom phase is all-inclusive; it’s a terrifying dissolution in politics, economics, and culture. For a high rate of inflation to occur in the US, you need both severe economic and political problems. High inflation in the US will ultimately be a political outcome, not an economic or monetary outcome. It will be, as in the Covid lockdown moment, a time when the economy is not well-functioning and therefore purchasing power is not what it was.

Oddly enough, I’ve been contemplating the concept of a Crack-up Boom all year. I believe that culture, economics, and politics are inextricably linked, and, for me, one of the most influential pieces of the year was Ted Gioia’s The State of the Culture, 2024.

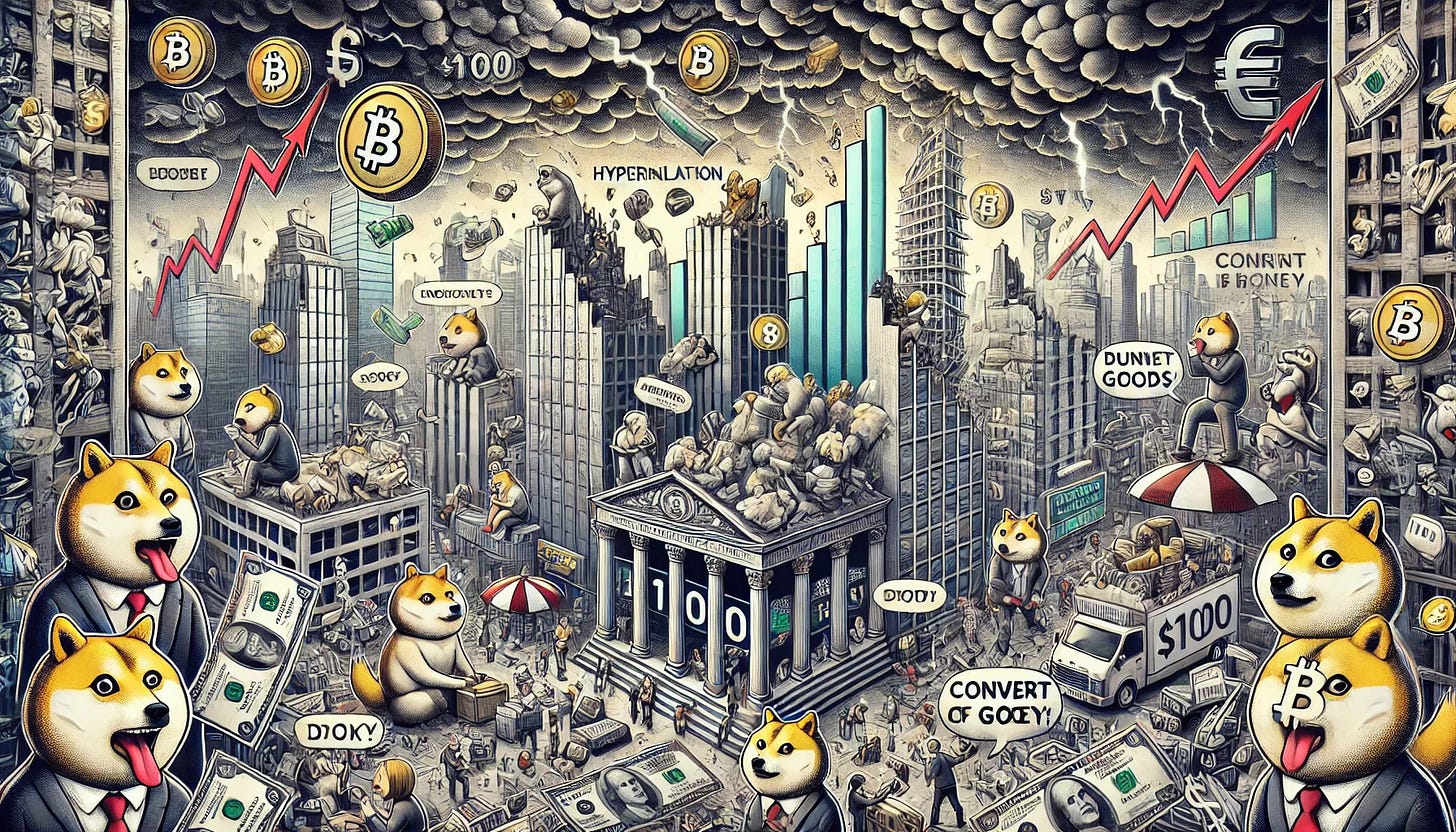

Gioia writes: “The fastest growing sector of the culture economy is distraction. Or call it scrolling or swiping or wasting time or whatever you want. But it’s not art or entertainment, just ceaseless activity. The key is that each stimulus only lasts a few seconds, and must be repeated.”

In Faster: The Acceleration of Just About Everything, James Gleick, writing in 1999, suggested that it was inevitable that the culture would move towards greater levels of stimulation over shorter frames of time. Gioia presents a brilliant graphic (below) that shows where the culture currently stands along this progression.

My belief is that inflation in the culture, as it were, is related to inflation in the economy. As the culture moves along the dopamine curve, the politics changes towards bouts of willful self-destruction, and the economics changes towards convenient short-term solutions that, such as aggressive fiscal and monetary policy, that tend to be inflationary.

Inflation in the culture makes people prone to quick-fixes in the economy. These quick-fixes — extreme fiscal spend and extreme monetary policy at the nearest hint of weakness — are themselves somewhat inflationary. The recent Congressional Budget Office projection (below) is scary, but not a guarantee of high rates of inflation.

It’s only when the politics breaks down that you get truly high rates of price inflation. I believe there’s a straight line from cultural impatience to quick-trigger economic stimulus to political breakdown.

Cultural impatience and a desire for quick fixes creates the political demand for aggressive monetary and fiscal policy. Some combination of bailouts, fiscal spend, or monetary ease rapidly follows any sign of weakness. The result is asset price inflation, which benefits the wealthy but not the poor, and inflation, which harms the poor. The position of the poor and middle class deteriorates significantly over time.

In the past, there has been a relationship between price inflation and a faster moving, more dopamine-fueled culture. It’s not fully clear which way the causality runs. It could run from inflation to the culture, as the inflation makes people somewhat more hedonistic. But it might also run from the culture to inflation, as a cultural quickening leads to a demand for quick fixes, which then generates inflation. In “Germany 1923,” Volker Ullrich argues that the causality ran from inflation to cultural decline. He notes, “Inflation dissolved traditional bourgeois notes of property much as it did obsolete ideas of morality.”

It’s worth noting that it’s not random that the X algorithm (in the For You feed) is littered with fight footage, even for those, like me, who previously followed nothing related to fighting or violence. Violence/conflict is the nth degree of stimulation, and the logical culmination of a dopamine-drenched culture.

A notable parallel between Germany and the US at present is that, in Germany, before inflation started truly galloping, there were dramatic increases in share prices that caught observers off guard, and the most speculative shares were observed to go up the fastest. Share prices, and especially the most speculative shares (which seem to act as a battleground for sentiment), sniffed out the incipient inflation before it found its way into consumer prices.

In The Economics of Inflation: A Study of Currency Depreciation in Post-War Europe, Costantino Bresciani-Turroni observed: “It was in the autumn of 1921 that business on the German Bourse reached such a condition as to put in the shade even the classical examples of the most violent fever of speculation. The technical equipment of the German exchanges was insufficient for the increasing mass of transactions.” Bresciani-Turroni cites a quote by Moriz Dub, also from 1921 but applying equally well today : “In the price sheets we find shares which have remained without yield for years and yet have the highest ratings. Imagination takes the place of calm calculation.”

The suggestion that our economic policy, which has led to high inequality, is likely to lead to extreme political dysfunction, which will in turn make our economic trajectory worse, might seem unfounded or dramatic. The Nobel Prize in Economics this year, in somewhat of a surprise, went to three economists, Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson, whose work has arguably focused on the relationship between economic inequality and political dysfunction. Simon Johnson wrote, in 2009, “The Quiet Coup,”in which he argued that the financial industry had effectively captured the government and that the United States was “Becoming a banana republic” with a well-entrenched financial oligarchy. He followed that up with the book 13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown. Neither work seemed to help his professional career much before the recent Nobel.

Stanford historian Walter Scheidel’s 2017 book, The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century, argues that “environments that were free from major violent shocks and their broader repercussions hardly ever witnessed major compressions of inequality.” He writes that inequality has tended to increase in history in the absence of what he calls the “Four Horseman of Leveling.” These are mass mobilization warfare, transformative revolution, state failure, and lethal pandemics. Early models by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson emphasize the importance of the threat of violence in instigating political change.

What would it take to avoid the Crackup Boom scenario over the next decade? I think we are a favorite, societally, to avoid the Crackup Boom scenario, but we are not a big favorite. Essentially we would have to navigate two treacherous paths. The first is economic. Although it is tremendously out-of-fashion, every sophisticated academic macroeconomic model has something called the transversality condition or “no Ponzi” condition that rules out infinite debt accumulation. Without the transversality condition, government in a model could set taxes to zero and keep borrowing to pay off interest, leading to explosive debt accumulation. It is not a constraint in the models per se, but rather a condition for optimality. It is possible, in a macroeconomic model or in the real world, to attempt to fund government with only borrowing, but the result will not be optimal. At a certain point, you will meet a “sudden stop” or “Ponzi moment.” In a future post, I’ll go over CBO projections in detail, but suffice it to say that, according to CBO projections, which are by many accounts optimistic (assuming, for example, the expiration of Trump tax cuts), upcoming deficits are dire enough that we are likely to flirt with “Ponzi moments” in the US debt markets. In John Cochrane’s Theory of the Price Level, price level inflation occurs at the moment unsustainable fiscal spending decisions are made, and I think that is the way to think about likely inflation going forward. Aggressive monetary policy is a lagged response to aggressive fiscal policy; the primary role of the Fed will always be ensuring smooth funding of the government.

The second treacherous path is political. Essentially, the consequences of the governments’ attempts to navigate an unsustainable fiscal situation have to be tolerated by the electorate. If the politics breaks down for any reason, then the economics breaks and you are in the high inflation/Crackup boom scenario. The politics breaking can take many forms. An extreme form of broken politics would be a non-peaceful transfer of power. Another form of broken politics would be the election of leaders who favored plainly unsustainable government finance. Perhaps the most likely form of broken politics would be a situation where the current model of responding to crisis (fiscal/monetary spend that inflates assets while increasing the price level, thus worsening the wealth divide) is pushed to its breaking point.

How does an individual navigate a possible Crackup Boom? Step by step is the likely answer. It’s almost impossible to plan for disrupted politics, or extremely bad economic states of the world. At the moment, one is left with a tough immediate choice: you can buy risky assets at extremely elevated prices in the hopes of shielding yourself (or even benefitting from) higher future inflation, or you can take little risk and bear the likely costs of high future inflation. I favor the lower risk approach at the moment, though those two options seem about fairly priced.

the 5d chess is if trump can crash the economy early in his term, he can bully fed into lowering rates and QE and east money and then we REALLLLLY get inflation but it has to hit early to get the next maga candidate (maybe Vance) elected.

inflation

-- 1) blame it on Biden

-- 2) bonds sell, treasuries fall, interest up

-- banks in danger

-- fed has to cut (sooner the better, this is where timing matters)

-- trump has been screaming at Powell to cut rates the whole time and fed has been saying nononono, so now it looks like j powell is Trump's bitch

-- if it happens soon enough, there is *benign* crack up boom. inflation up but stocks also up, inflation up, shit is popping. More on the "benign" part later.

-- "Trump rescued the economy!"

-- Maga party wins the midterms 🐦🔥🇺🇸

-- Powell can't cut rates now, too much danger to banks

-- Vance 2028

This was somewhat incoherent, in the underpants gnomes sense of there being a missing step.

Somewhere between "crack up boom", "Maga wins 2026" and "Maga (vance?) wins 2028" four years have to pass.

The boom part wins the midterms. The crack up is where things get tricky. Traditionally this means hyperinflation in the weimar sense. I think (and I think most people think) we may get lucky and have merely uncomfortably high inflation with mild social unrest rather than the full on disaster.

The dilemma for powell is helping banks enough to avoid a panic, without helping them so much that he is perceived as purely trump's bitch in which case ten years go above 5% (maybe 6%) and we begin to enter into the weimar disaster because you have to keep issuing more debt to service the existing debt and it compounds.

The dilemma for trump is similar. He needs to maintain access to credit, with buyers of bonds. Too easy on powell, economy stagnates, young men have too much time on their hands watching porn, start planning protests and setting cars on fire. But too hard on powell, ie perceived threat to nominal independence of the fed, bondholders sell 10 years and buy gold and bitcoin. No more credit. Capital controls, who knows maybe rationing, young men may also revolt in some unpredictable way that threatens Maga.

So it's like a dance / sumo wrestling match between two old guys, with obese trump circling svelter and somewhat more agile (but still old and creaky) powell, they're both kind of grabbing at each other but missing, and they circle and circle and nothing much happens.

Oh, and meanwhile while trump and powerll are having their MMA cage fight, democrats are watching horrified and saying MMA should be made illegal, but also hypnotized and fascinated, the end result being they also continue to do nothing.

That's the optimistic scenario.

I think there is the inklings of a plan by tech Maga to help find buyers for treasuries, by broadly enabling growth of stablecoins for randos internationally (so anyone, angola or argentina, doesn't matter) can nominally own dollars.

Poor angolan goat herder owns tether, tether owns 10 year treasuries. I think that's the plan.

Tether and usdc combined is 200 billion/36,000 total debt.

If tether (or all stablecoins combined say) grow 5x to 1 trillion, this is now funding 3% of federal debt. That's still a small amount, but the marginal buyer is important.

So maybe that is what trump would like to do. Grow usd stablecoins 5x, before he has to refinance.

When you are way in debt and looking for credit, every little bit helps.

Maybe it'll work long enough to keep the crack up inflationary, but not hyper inflationary. At least long enough for Maga to survive trump and pass the mantle to someone new in 2028.

I am a little puzzled by this piece, because it doesn't deal with the increase in money supply at all, which is the most important inflationary factor...